Inside TVA’s Nuclear Future: A Tour of Sequoyah Nuclear Plant

An inside look at how Sequoyah powers 1.3 million homes and anchors TVA’s growing nuclear corridor across the Valley.

Driving to the Sequoyah Nuclear Plant, the power lines multiplied with every mile. But what truly marked the approach was rounding a curve and seeing the cooling towers — two colossal stacks of concrete — rise into view. No steam drifted from them that day, the river conditions didn’t call for it, but the sight alone conveyed the scale of human engineering.

On Tuesday, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest public utility, invited reporters to tour the Sequoyah Nuclear Plant in Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee. Sequoyah is one of three operating nuclear plants in the TVA’s fleet. The tour showed how the plant operates and how TVA plans to keep it running for decades. It also detailed the work in each refueling outage, the realities of nuclear fuel and waste, and the Valley’s growing role as a national corridor for nuclear power.

Inside the Reactors

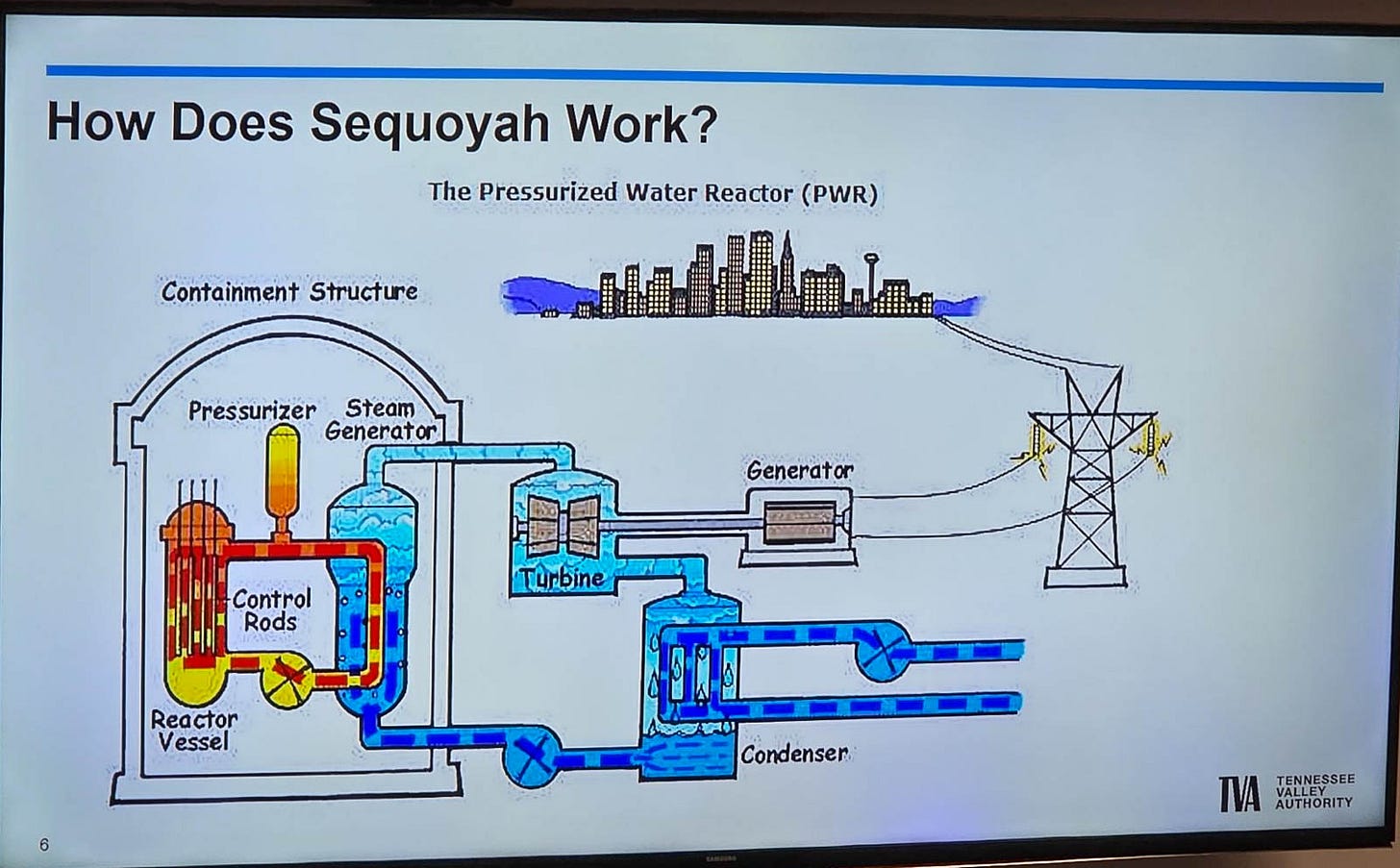

Sequoyah operates with two pressurized water reactors, known as units 1 and 2, which together supply power to approximately 1.3 million homes. It runs on a three-loop system. The primary loop carries reactor-heated water through steam generators. The secondary loop turns that heat into clean steam to spin the turbines, then condenses it back into water to repeat the cycle. The tertiary loop draws from the Tennessee River to cool the turbines’ excess steam, returning that water safely to the river through the cooling towers.

One unique feature of Sequoyah is its ice condenser containment design. Operations director Keith Stephens explained:

There is a refrigerator that runs the circumference of the exterior of the containment structure. It’s inside, but it’s on the outer perimeter of the wall and that’s there to mitigate any potential accidents that may occur, and allows the temperature and the pressure inside the containment vessel to remain within design limits.

“There are five ice condenser containment designs throughout the country,” Stephens added. “Sequoyah and Watts Bar are two of those.”

Extending Plant Life

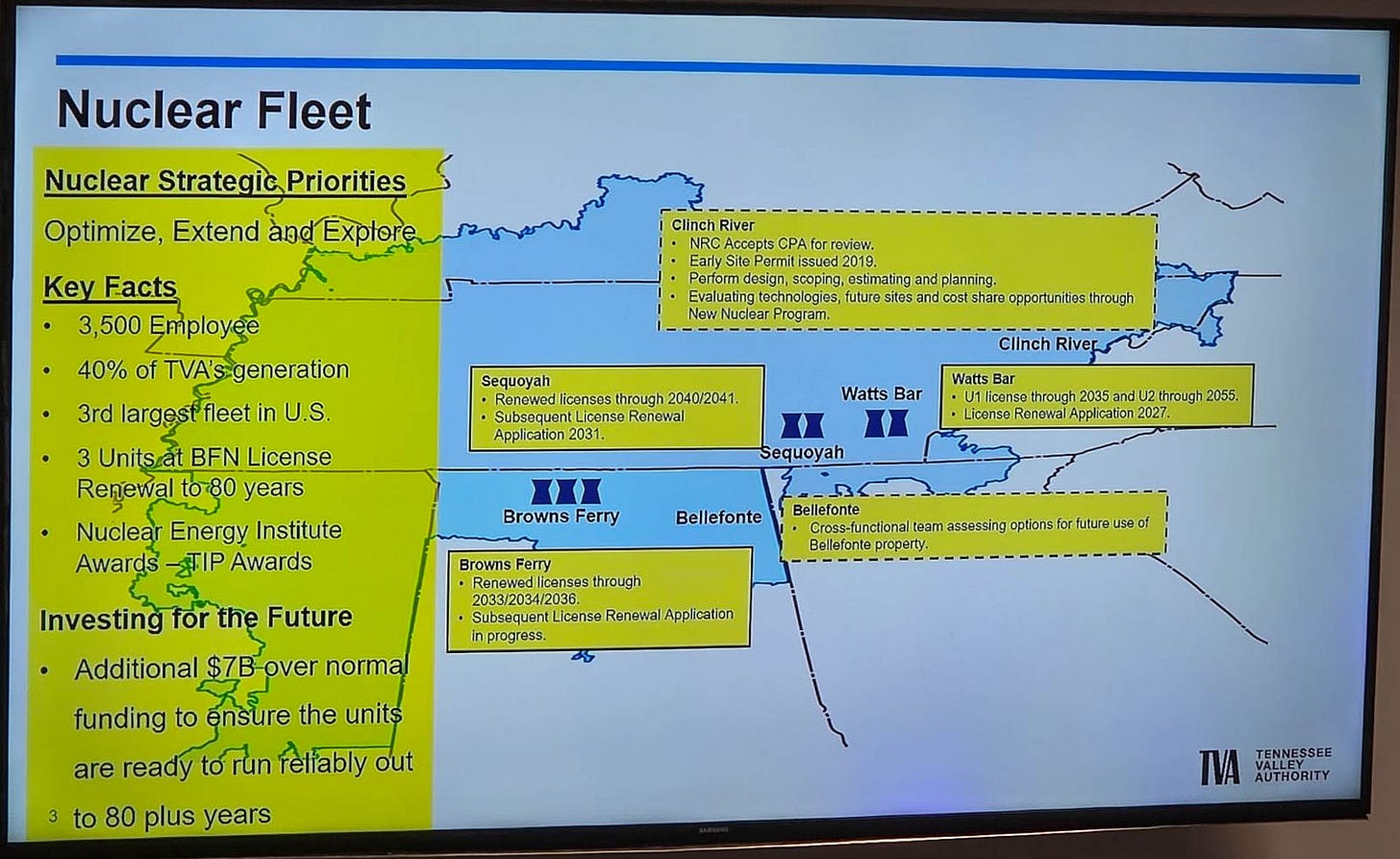

When Sequoya’s two units came online in 1981 and 1982, they each carried a 40-year operating license. In 2015, those original licenses were extended to 2040 and 2041. Now the TVA is preparing for “subsequent license renewal” which could extend plant life to 80 years.

TVA’s incoming chief nuclear officer, Matthew Rasmussen, said Browns Ferry in Alabama is expected to be the first plant approved under the new process. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversees license renewals. “We expect to get our first license extension at Browns Ferry this fall from the NRC, which is months ahead of schedule,” Rasmussen said.

Refueling and Repairs

Despite their longevity, Sequoyah’s reactors require regular and precise maintenance. Stephens said:

Every 18 months we bring each one of the units offline for refueling. … We will supplement our workforce by roughly double.

The next outage begins October 3. Stephens said crews will replace a third of the reactor’s fuel, swap out major components and “log around 130,000 person-hours of work.” The shutdown will last about 48 days.

Rasmussen emphasized that outages are planned for minimal customer impact:

We do our outages in essentially the fall and the spring where electricity demand is already low. We don’t want to do refueling outages in the summer, when we’ll have over 30,000 megawatts.

Rasmussen’s point about summer demand became clear once inside the turbine building. Even on what TVA staff described as a “cooler” August day, the temperature inside hit 105 degrees. A thermometer hanging in the building made the heat hard to ignore. Even the railing on the steps felt hot to the touch as we climbed.

That environment stands in sharp contrast to the plant’s control room. Operators there work in a space that must remain air-conditioned at all times, not for comfort but for reliability. The equipment requires a stable, cooled environment to function properly. Reporters had to remove their protective equipment and secure any dangling items before entering, underscoring just how different the conditions are between the two settings. From this room, operators manage the reactor itself, ensuring the plant runs safely and without disruption.

Managing Spent Fuel

If the tours dispel one myth, it’s about nuclear fuel. A single uranium pellet — “about the size of the tip of your finger,” Rasmussen said — produces as much energy as 2,000 pounds of coal. All the spent fuel from Sequoyah’s four decades of operation fits on a concrete pad about the size of a football field.

“It’s not this vast expanse of used fuel,” Rasmussen told the room of reporters. He added:

It’s a very small footprint in comparison to the amount of energy the site’s produced over the last 40 years.

Building the Valley’s Role

Beyond Sequoyah, TVA is positioning the Valley as a national hub for nuclear power. Rasmussen described a “corridor of nuclear power” stretching from Browns Ferry to Oak Ridge, Tennessee calling it, “a hub and spoke model for the entire country for nuclear power.”

That corridor includes TVA’s partnerships with Kairos Power and Google on next-generation reactors, as well as new fuel enrichment investments in Oak Ridge. Today, about 40% of TVA’s generation comes from nuclear, double the national average.

The conversation everybody should be having is, why not more nuclear power?

said Rasmussen. “We’re seeing great public support. There is a high capital investment on the front end, but the cost of operating is low, the reliability is extremely high.”

Before concluding the tour, Rasmussen shared a personal reflection.

He remembered his own trip to Browns Ferry as a college senior headed to an interview for his first job. “There was no GPS, and I got so lost,” he said. “I just found a power line and thought, well I’m going to follow this power line to see where it goes. It took me right there.”

His story showed how TVA’s transmission lines still guide newcomers and the region’s energy future.

On the drive to Sequoyah, similar lines marked my route. They also map a bigger idea taking shape across the Valley: reactors built to last for decades, scheduled outages that keep them reliable, and a nuclear corridor stretching from Browns Ferry to Oak Ridge where new partnerships are taking shape.

As TVA spokesman Scott Fiedler put it:

Electricity now is the strategic commodity. It's no longer oil or steel or gold. It is electricity that builds all of those things, because if we don't have power, we're back to throwing rocks at one another.